I wish so many of my father’s stories hadn’t remained unspoken.

Learning

It was in the early hours of November 11, 2022, that my 92-year-old father died in Toronto with my mother in a chair beside him.

The significance of the date of his passing didn’t strike me until later that day. It was Remembrance Day. A hundred and four years after the end of the World War I, what was supposed to be “the war to end all wars.” Except that it wasn’t.

My father was a Canadian child of World War II internment of Japanese Canadians, dispossession, and forced expulsion. Fingerprinted and registered, they were issued ID cards to restrict their movements. His family was incarcerated in Tashme, the largest of eight internment camps of uninsulated tarpaper shacks, hastily built specifically to contain over 2,600 British Columbians of Japanese ancestry. Isolated in a narrow, heavily forested valley and surrounded by the high Cascade Mountains, Tashme was as good as a prison.

White rice was rationed during the war, and when a supply arrived in Tashme, it was mixed with rough barley to make it go further. To my father, this unpleasant grain mixture was the taste and texture of internment. Short-grain rice is supposed to stick together, not fall apart, its texture smooth and even.

World War II officially ended in 1945. Yet, no longer officially enemies, interned Canadians of Japanese ancestry remained alien in their own country of birth and still persecuted. When the war ended, BC and Canada made sure they were not allowed to return to the West Coast where my father and his siblings were born, so the family, now homeless, moved to Ontario rather than be sent to war-ravaged Japan. There was no more pretense that Japanese Canadians had been incarcerated as wartime national security threats.

Landing in Scarborough, Ontario, because the city of Toronto would not let them disembark from the train, my father’s family were unwanted asylum seekers in their own country. It wasn’t until 1949 that fingerprint identification cards were no longer enforced. As soon as he could, my father burned his ID card, a hated symbol of Canadian racism that superseded his Canadian birth certificate.

I wish I had asked him to say more while he was still alive. I wish I had asked him how he learned to deal with the anger of injustice that had shaped the arc of his family story. I wish so many of his stories hadn’t remained unspoken.

“Very truly, I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies it bears much fruit.”

John 12:24

Grief comes in waves.

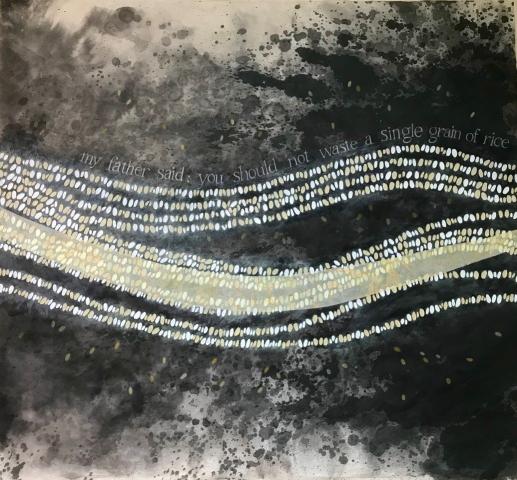

“An Inheritance of Activism,” a national Japanese-Canadian human rights symposium in 2022, showcased a powerful installation by Lillian Michiko Blakey, a gifted Japanese-Canadian artist. Entitled Sticky Rice, her 15-foot drawing depicted a geographical and chronological wave of 22,000 grains of rice, each grain representing a Japanese Canadian who endured injustices of forcible WWII uprooting, forced labour, family separation, incarceration, exile, and dispossession, and honouring those who died along the way.

Blakey’s artistic wave forms a loosely connected shape of a dispersed community with a tightly bound core throughout the centre of its journey. Her art piece is as much a relational journey as it is geographical and chronological.

Dr. Masao Takenaka, Japanese ecumenical theologian, wrote a little volume on Asian culture and Christian faith called God Is Rice.* In Takenaka’s theology, rice, the main staple of Japan, is an enculturated symbol of God’s gift of life and symbolic of the whole of creation.

Short-grain rice sticks together, especially when hot and pressed together. “Sticky rice” is a powerful metaphor for a targeted and exiled community forced together under the pressure of fear mongering, race hatred, and abusive political power. God’s gift of life is not just for one community or one moment in time but for all people, all the time: refugees fleeing wars, displaced persons, asylum seekers, immigrants leaving political oppression, and persecuted 2SLGBTQIA+ people.

Twenty-two thousand began the exile journey. My father is no longer among the 6,000 or so internment survivors still living. And yet, the wave continues, a community lives on.

This coming Remembrance Day I will have a new reason to pause, not only to honour those who died in the line of duty but also to honour those civilians who survived wars as collateral damage, and those who died with stories unspoken.

Faith Reflection

Prayer

Eternal One,

For all your beloved children

rejected, vilified, exiled, displaced,

we invoke your blessing.

Bless the attentiveness of our listening

that we might receive your voice

in the silence of unspoken stories.

Bless the softness of our hearts

that we might welcome the world’s dispossessed

who have nowhere to feel safe.

Bless the ebb and flow of our journeys

that our communities hold together

and no one is left alone.

And may you draw us every closer to life.

Living It Out

Reflect on the following questions:

- Who are those in your community who have been forcibly displaced and homeless? Unjustly incarcerated? Collectively targeted because of their race or gender or identity or religion?

- How are you learning their stories?

- In your own community/family ancestral story, when has there been chosen or unchosen displacement, expulsion, or homelessness?

- How have those stories been told or not told to you?

- If you could depict your community’s story in art form, what shape would it take?

—Kim Uyede-Kai (she/her) serves as Shining Waters Regional Council Minister for Communities of Faith Support, Right Relations, Intercultural Diversity, and Anti-Racism. She also serves as Vice-President of the Greater Toronto Chapter of the National Association of Japanese Canadians.

*Masao Takenaka, God Is Rice: Asian Culture and Christian Faith (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2009).