Can you be both queer and Black, and enjoy a celebrated and visible presence in the United Church?

Gender identity and sexual orientation don’t exist in a vacuum. Both are powerfully shaped by racial privilege and oppression. We asked several LGBTIQ2S+ members of The United Church of Canada to reflect on how race complicates the search for social justice—and on the challenges of finding welcome in the church if you are marginalized in more ways than one.

A decade ago, the doors of The United Church of Canada were flung open for me, and it was with deep gratitude that I stepped across the threshold, assuming that all of me was welcomed. However, to fit in I needed to cleave myself into three separate pieces: queer, Christian, and Black. Space has been made for the queer piece of me, and the whole context exists to house the Christian piece. The haunting question lingers: Is there room within the United Church for my Black body? Because too often, my experience has been that there is not room for my Black body, even as my queer one is affirmed.

And if as an ordained professional I experience this cleavage—if I am compelled by systemic White supremacy and classism to divide my very self—then I wonder about the lived experiences of my queer Black relatives who seek spiritual and pastoral care from the United Church.

Two decades ago, I began hearing stories from Black LGBTIQ2S+ folks about their experiences of visiting Affirming United Churches in Toronto. The dominant narrative then, as it is now, was that the United Church is not a place of welcome or affirmation for them.

One story still stands out. A queer Black young man recalled how on his first visit he had a visceral sense that he’d be tapped on the shoulders and someone would say, “Get that Black body out of here,” but he persisted and visited that congregation thrice in three months. On his second visit he said that a kindly gentleman offered an enthusiastic greeting: “Welcome. We didn’t expect you again because folks don’t usually return.” He did not ask whom the folks were who did not return. On his third visit he said that each sign of the peace communicated, “There is really no need to come again. We know this won’t be home for you.” And he never did.

I resisted the repeated narrative shared by queer Black folks that certain actions, attitudes, and structures—basically Whiteness and its multiple barriers—make the United Church inaccessible unless one is willing to fit into a box with queer White folks.

Without challenging our hard-won commitment to gender justice, which is firmly rooted in excellent theology, I resist the tendency to assume that the conversation is finished because the dominant White church has “won the battle.” In our important focus on welcoming LGBTIQ2S+ folks into the church and ministry, perhaps there is a race issue festering alongside that focus that has gone silent, or at least has been smoothed over in a very Canadian way. Yes, you can be queer in The United Church of Canada.

But can you be both queer and Black, and enjoy a secure, nourishing, celebrated, and visible presence?

There can be no hiding from real conversations about race, spirituality, queerness, and Blackness within the United Church. I refuse to be invisible, especially because anti-Black racism in the church is not overt—it’s more like an omission that, in the Canadian way, the church hopes might simply disappear with time and silence. But neither will heal it. It will not go away if we do not talk about it.

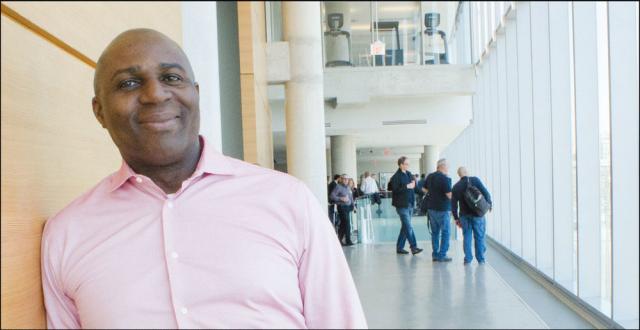

— Basil Coward is a queer Black writer, minister, and psychotherapist.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2018 issue of Mandate magazine.